The Worst of British Cooking: School Food in the 1950s

I've spent half a century (yikes) writing for radio and print—mostly print. I hope to be still tapping the keys as I take my last breath.

In 1945, George Orwell wrote that, “It is commonly said, even by the English themselves, that English cooking is the worst in the world.” He then went on bravely to defend the island’s chefs, listing such delicacies as kippers, treacle tart, and suet pudding.

More recently, food writer Bill Marsano gave his opinion that “All in all, I think the British actually hate food, otherwise they couldn’t possibly abuse it so badly.”

The same gentleman rendered the opinion that the nation’s cooking was the reason why the United Kingdom was such a major world power for a while: “The British Empire was created as a by-product of generations of desperate Englishmen roaming the world in search of a decent meal.”

Such negative views are mostly in the past, but they cannot extinguish my own anguished schoolboy memories of British cooking in the 1950s.

You cannot trust people who have such bad cuisine. It is the country [Great Britain] with the worst food after Finland.

— Jacques Chirac, Former President of France

The Horror of School Dinners

English schools provide a meal to students at lunchtime, so, of course, they call it dinner. Brits are like that with their own language.

The place of learning to which I was sentenced for ten years during the 1950s was a minor public school for boys; again, the perversity of the language raises its head—public schools, as they were then known, were private. The school did not have the prestige of Eton or Winchester, but what it lacked in status it made up for in the gruesomeness of the food it served its students.

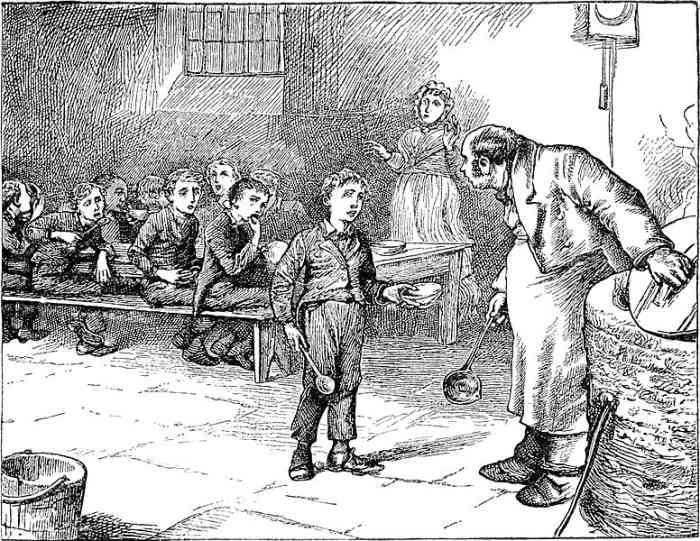

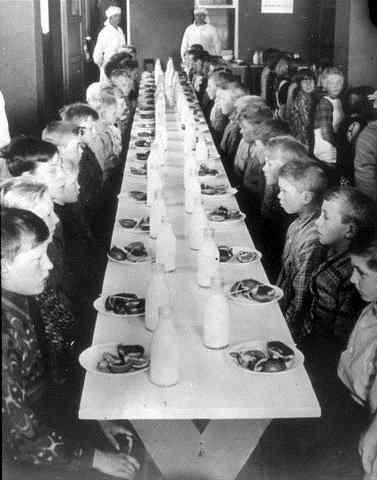

Tables were set out in long rows in the dining hall, although the word “dining” is highly inappropriate. Students sat on benches creating a tableau that might well fit into a Victorian workhouse. And, the proceedings got underway after grace was said in Latin.

The basic philosophy behind the meals was that the food had to be stodgy enough to repel the cool damp that is the British climate. In the process, it also repelled the people forced to eat it.

A staple was stew. All the boys knew with complete certainty that the protein content, liberally laced with gristle and fat, was provided by whales. Okay, so that was probably not the source. Given recent revelations of horsemeat getting into Europe’s food supply chain, I have suspicions about the provenance of the meat.

Anyway, the stew was a vile, grey swill and was usually served with mashed swede (rutabaga in North America, neeps in Scotland), or cabbage boiled to a bitter mush, and mashed potatoes with large lumps lurking in the heaps.

There are ways of cooking swede to make it delicious; the addition of butter, apple, and nutmeg are mentioned. But, such refinements were a mystery in the kitchens of my school; their wisdom was that swede needed to be boiled for hours until it reached the acrid consistency of gruel before serving it to the inmates.

To eat well in England, you should have

breakfast three times a day.

— W. Somerset Maugham

On Fridays there was fish. Slabs of cod (perhaps) floated in a yellowish, pallid, and oily residue. The cod was flecked with tiny black threads that meandered through the flesh and which were widely known to be some sort of parasitic worm. No chips with this, just more lumpy mashed spuds.

And then there were Spam fritters. It is not possible to fall farther off the Epicurean wagon than coating ground up pig’s eyeballs, ears, and whatnot in batter and deep-frying it in a boiling vat of beef tallow. Shudder.

Even the cooks find Spam fritters disgusting.

Sometimes in the summer term salad showed up. Salade Nicoise? Non. Insalata Caprese? No. Crab Louie Salad? Naw. What we got was limp lettuce turning brown at the edges with always the chance of finding wildlife lurking in the darker recesses – small beetles, larvae, or, the worst discovery of all, half a caterpillar. Salad dressing? Forget it.

Dessert was almost invariably one of a series of grim milk puddings – rice, semolina, or tapioca. The rice pudding was a horrible confection that always contained large blobs of congealed starch that were thick enough to stop a bullet.

Occasionally, they would throw into the rotation – Oh! The humanity – a vile concoction of stewed prunes and figs; served up on the premise that a boy with healthy bowels was a boy with a healthy mind.

Surely, he exaggerates. Read on.

What passes for cookery in England is an abomination ... It is putting cabbages in water. It is roasting meat till it is like leather. It is cutting off delicious skins of vegetables ... A whole French family could live on what an English cook throws away.

— Virginia Woolf

Widespread Disgust

In 2003, the BBC’s Good Food magazine surveyed more than 2,000 people who had stoically endured school dinners. The result was that “Tapioca is the most hated school food of all time … cabbage, overcooked vegetables, lumpy mashed potato and, lumpy custard closely followed ...”

More than half of the respondents (51%) revealed they had “been so scarred by school dinners that the experience still affects their everyday eating habits.”

The Guardian reports that many of those surveyed recalled the nicknames they had for what appeared on their plates: “The school slang of the time resurfaces in answers to the school dinner survey—custard was ‘cat sick,’ peas were nicknamed ‘bullets,’ and Spotted Dick (sponge pudding with raisins) was better known as ‘fly cemetery;’ ” to which can be added semolina with a dollop of jam in the middle of each bowl known as “nose bleed pudding.”

Bonus Factoids

Denis G. Campbell is founder and editor of UK Progressive magazine. Here are some of his descriptions of what food was like in Britain in the 1950s:

- Pasta had not been invented.

- Curry was a surname.

- Olive oil was kept in the medicine cabinet.

- The only vegetables known to us were potatoes, peas, carrots, and cabbage.

- Brown bread was something only poor people ate.

- Figs and dates appeared at Christmas, and no one ever ate them.

- Hors d’oeuvre was a spelling mistake.

- Nothing ever went off in the refrigerator because we didn’t have one.

- Surprisingly, muesli was available in those days; it was called cattle feed.

For more than 20 years, a London restaurant has been using school dinners as its theme. Unsurprisingly, the eatery is called School Dinners and offers “good, old-fashioned British grub. A selection of specially made English sausages, (including a vegetarian option) and mash, home made pie of the day, roast beef followed by traditional spotted dick and custard.” Although why anyone would feel a nostalgic tug to the place is a complete mystery to me.

Sources

- “Tapioca Tops BBC Good Food Magazine’s ‘Most Hated’ School Dinners Survey.” BBC, July 8, 2003.

- “Tapioca Voted Worst School Dinner.” Donald MacLeod, The Guardian, August 6, 2003.

- “British Food in the 1950s.” Denis G. Campbell, UK Progressive, January 11, 2013.

- Schooldiners.com

© 2017 Rupert Taylor

Comments

Jaden Holley on November 08, 2019:

I cannot agree more

Rupert Taylor (author) from Waterloo, Ontario, Canada on November 06, 2019:

Jaden and that's just reading about it. What about us poor wretches who had to eat it? Grrrsnort.

Jaden Holley on November 06, 2019:

holy crap this food makes me wanna hurl

Rupert Taylor (author) from Waterloo, Ontario, Canada on March 01, 2019:

Hi Richard. Happy to have you quote some of my article.

Richard Bown on March 01, 2019:

Brilliant - takes me right back to my days at a boarding school in the late 1950s. I am writing a family history blog, Gerrard 1813, and this describes exactly my experience. May I quote some of it or cut and paste some extracts into a post?

Glen Rix from UK on February 20, 2017: